Let's talk about the book with the funny looking Ludwig drums with the Silver Dot heads on the cover— and all the ugly Paiste ColorSound cymbals, and Simmons SDS-5 hexagonal drum pads.

Yes, I'm talking about

The New Breed, by Gary Chester. It's one of the big hard books the drumming community likes to talk about. While it hasn't been universally adopted— lot's of people, like me, don't use it, have never used it— it has been very influential in developments in drumming since the 90s. It's a coherent grand system for playing the drums created in a time when there weren't a lot of coherent grand systems for that.

The book became a thing coinciding with Dave Weckl— who studied with Chester— becoming an extremely hot drumming item in the mid 1980s.

“Every time I'd walk into a lesson, he'd come up with a different system, and I'd feel r___ded. Then I'd go home, practice it, and get it down to where it was cooking. When I'd go back, he'd tell me something else to do with it, and I'd feel r___ded all over again. It was great though; his lessons are such a challenge.”

After Weckl, there were a series of smaller drumming sensations— e.g. Joel Rosenblatt— who came out of Chester's studio, that cemented this as a thing to do. In more recent years the open handed drumming thing has really taken off, and this is one of the first books that advocated that in a serious way.

So let's look closely at what's in it. If you don't own it, you can certainly find pirated pdfs online to look at while you read this.

But buy it. It's $18, nothing.

In the Concepts part of the book, pp. 4-7, Chester lays out his doctrine:

- Learn everything on the drum set both right hand and left hand lead.

- Use a funny set up, with hihats, ride cymbals, and floor toms on both sides.

- Each hand stays on “its” side of the drum set.

- Singing and counting— do it, sing each of the parts while playing.

Everything that follows is in aid of those first three points, as the best vehicle for creative reading and groove making on the drums. If you agree with those priorities, you can commence working your way through the book in order. If not, you might want to be more selective in how you use it.

There are 39 systems— combinations of repeating rhythms for three limbs— to be played while reading an independent melody part played with the fourth limb. The reading is not unlike what is in Syncopation, first with 8th note based rhythms, then 16th notes. The advanced reading pages are built on repeating two measure phrases.

The systems mostly follow standard pop timekeeping conventions of backbeats on the snare drum / ride rhythm on a cymbal. All systems have a right hand lead form, and a left hand lead form— 50% of the materials are dedicated to learning to play time “open handed.”

Here is what is generally happening with them:

- System 1: A warm up, with the hands playing unison 16ths on the hihats.

- Systems 2-13: Conventional forms of timekeeping, combinations of simple cymbal and left foot rhythms, bass drum plays melody.

- Systems 14-15 and 18-19: One hand covers the cymbal and snare drum with the bass drum playing the melody, then the other hand playing the melody.

- Systems 16-17: Hands play alternating 8th notes between a floor tom and cymbal, with the bass drum playing the melody.

- Systems 20-25: Simple, unusual, coordination problems.

- Systems 26-29: Advanced, but conventional, timekeeping combinations.

- Systems 30-39: Conventional timekeeping combinations with the left foot independent.

Summarizing which limbs handle the independent parts— mostly bass drum, a lot of left foot, a little bit with each hand.

- Systems 1-17 and 22-29: bass drum

- Systems 18-21: a hand on a floor tom

- Systems 30-39: left foot

Getting into the advanced systems starting on p. 24:

- Systems 1-4: bass drum independence vs. particular, unusual linear pattern in the hands.

- Systems 5-6: bass drum independence vs. a basic fusion cymbal rhythm with backbeats.

- Systems 7-8: hand independence vs. basic fusion cymbal rhythm plus alternating 8ths in the feet.

- Systems 9-10: bass drum independence vs. the linear pattern above, played with an alternating sticking.

That linear pattern, which is used on several systems, is a little strange, I don't understand the logic for for having that be the one thing of its type:

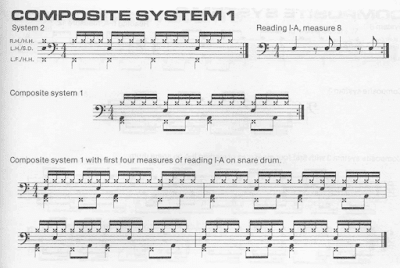

Things get vastly more complicated with the composite systems starting on p. 38. There you basically extract one measure from all the playing you did in the first part of the book, and replace one of the system parts— playing all the reading pages with that part.

That's an order of magnitude more difficult than anything done so far, and virtually endless. This is the spot in the book I would like to see much more fully developed, finding a middle state between the simple (but very demanding and time consuming) first part, and the vast, extremely difficult second part. Suggest some more practical rhythms for the new complex part of the ostinato.

Which we kind of get here, with a standard pop or bossa rhythm in the bass drum, that is only slightly more complex than everything in the basic systems:

After that the composite system examples are kind of random. Personally, I would want to pick and choose the new part for practicality, and would like to have seen that reflected in the book.

My brief experience with it:

After writing most of this post I decided to sit down and actually play some of it, so I went through the first five systems— including the

“open handed” ones— with all eight pages of reading, counting quarter notes out loud. I've never worked on learning to play open handed, but it was basically easy after doing the

harmonic coordination stuff from Dahlgren & Fine, and

my own related system. It became kind of an endurance exercise. As after doing any kind of serious endurance exercise... things move a lot easier when you're done, even things not covered in the exercise. It was cool.

It had that result for me, I think, because I've been playing for a long time, and have a lot of real playing content under my belt, and a developed musical ear. This is not an ideas book; if you don't have any ideas in your ear, it won't provide them.

I also ran all eight pages of reading for left hand independence in a songo feel, and I do like the reading pages for that, and for the intended purpose running Chester's systems. They're well constructed to be progressive in difficulty and challenging, but not ridiculous— the ridiculous part is in how they combine with the systems.

Thoughts:

The playing theory here is actually rather primitive, dealing with “pure” independence, based on layering unrelated rhythms, rather than interdependence, with the parts connected and based on each other. Certainly that will be learned in some form while learning the systems, but it's not addressed directly in the method itself.

The singing element seems to be a key part of this method, and you can actually do that with anything you practice— sing quarter notes, then offbeat 8th notes, then each of the parts of the pattern. Certainly that's possible with all the

Syncopation systems.

Making any kind of serious effort with this book would be a big deal. Certainly there will be hidden benefits beyond just learning the resulting patterns as vocabulary, as I observed above. Your concentration will certainly be improved— Chester mentions that, and Dave Weckl in his interview. I've noticed the same thing with other hard materials. It would be a massive journey, and there will be results you don't expect.

Some perspective:

I suggest reading

Scott K. Fish's 1983 interview with Gary Chester. At that time, as this book was being written, Chester's studio career had ended about ten years earlier, and he had been teaching drums about six years— a very compressed timeline for developing this method. He's a forceful communicator and talks very intensely about his 20+ year studio career, and it's clear that that is his main orientation as a musician and a teacher. He states that his motivation with the book is for players to be able to do the impossible when it's asked of them on a recording date, or other demanding professional situations.

It's also clear that he wasn't teaching it to all levels* of drummers— his students were highly ambitious, motivated players. He mentions firing students who weren't performing the way he wanted, who he felt would not represent him well as a teacher.

[* - Update: Or was he? checking out some videos from his former students, a couple of them started with him when they were kids, and actually doing a very simplified form of the method here— the same principles, anyway— applied to Haskell Harr.]

So, I think the book serves a narrower purpose than is often assigned to it today, as it's a popular item with enthusiasts, who are fascinated with ambidexterity, and have fixated on it as a manual for reinventing the drum set. To me it looks like less of a grand theory of drumming, or a system for initially acquiring vocabulary, and more like a very large, brutal— and somewhat arbitrary— conditioning regimen for professionally-bound drummers.

You don't start by crawling up Everest. The way most drummers develop is, they learn a lot in a few years. I started playing when I was 12, and played my first paying gig when I was 18, and I was a slow starter. You learn a lot very fast, and then spend the next ten years cleaning up after yourself, which I think is what this brutal slog of a book is for.

.jpg)

.jpg)